Founders All

Every End is a Beginning

It feels like things are falling apart. Over the first half of 2025, the slow background entropy of our world has been set to 4x speed as the Trump Administration and its enablers have gleefully embraced the mantra: “go fast and break things.” Amidst the chaos and harm, it’s easy to see what’s happening as a collapse, a crisis, a disaster. This catastrophic framing is apt in many ways–lives are being destroyed, economic security is being undermined, families are being torn apart, and the institutions of civil society are being dismantled. Amid the rampant pain and casual cruelty of it all, it is easy to see all that is being ended and broken, but it can be harder to see the beginnings that must be around the corner.

It is unlikely that we are living at the end of human existence (though, of course, not impossible) and it is also unlikely that we are living at the end of the United States (though, again, not impossible). This means that if the chaos around us is the collapse of something, it must also be the birth of something else. In other words, amid the ruins of an old sociolegal order and amid the rampage of a venal nihilistic bully, we find ourselves in a founding moment.

Whether we like it or not, in this founding moment all of us have become founders. It is easy to feel disempowered or to feel as though whatever is happening is an abstraction at a distance from our own lives. But in reality, politics and civil society (or the lack thereof) are built from our collective daily work, play, despair, and imagination. That means that we are all in some way accountable for the collapse we are living through and that we are all building what comes next together.

As we take up the mantle of founders, we can learn a lot from looking backwards to another moment of end and rebirth: the two decades between 1850-1870. As corrosive politics around slavery destroyed the fragile compromise of the first half-century of American sociolegal order, people who had been comfortable became radicalized, and people who had been content to be governed by others increasingly realized that they, themselves, had to be founders.

Repose and Radicalization

In 1854, Henry David Thoreau watched (from a distance) in horror as Anthony Burns was marched through the streets of Boston by federal troops at bayonet point toward a boat waiting to take him south and to enslavement. Thoreau had lived his whole life in a world permeated by the politics, economy, and culture of slavery. For most of that life (including the time he spent philosophizing on Walden Pond), he had been an opponent of slavery in the abstract, but he held the radicalism of abolitionism at a distance. Even when he wrote his famous essay on “Resistance to Civil Government” (what would become known as “Civil Disobedience”) in 1848, his focus was on the violence of the state in a more abstract sense, with slavery as one salient example. Thoreau, like many elite northerners living in the first half of the 19th century, was anti-slavery but not yet radicalized. Within a (relatively) stable legal and political culture most people like Thoreau were critical but comfortable.

For Thoreau and many others in Massachusetts, that comfort was ruptured by the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 which created explicit federal judicial and law enforcement infrastructure to help people who claimed ownership in other human beings capture and enslave those they claimed to own. This rupture culminated in 1854 when Anthony Burns was arrested and relegated to slavery by federal commissioner Edward Loring (who was also a lecturer at Harvard Law School). Abolitionists in Boston had already tried to rescue Burns once–and in the process they’d killed a federal marshal guarding him in prison. Taking no chances with further escape attempts, federal authorities called in troops to march Burns from the courthouse to the harbor under military guard.

This spectacle, witnessed in person and vicariously through the fevered press coverage, was a radicalizing event for many. Some conservative elites who had been complacent about slavery were galvanized against slavery overnight. In the words of textile baron Amos Lawrence, “we went to bed one night old-fashioned, conservative, Compromise Union Whigs and waked up stark mad Abolitionists.”

In this context, Thoreau’s 1854 essay, Slavery in Massachusetts was one among many statements of radical intent and transformation. Seeming to awake from his abstract critiques into something more immediate, Thoreau wrote: “It is not an era of repose, we have used up all our inherited freedom. If we would save our lives, we must fight for them.”

These are words that keep cycling back into my brain as we navigate our way through a world where all zones are being “flooded with shit” at all times and where institutions and understandings that have long seemed stable are crumbling into instability and uncertainty all around us. If we ever lived in an era of repose, more and more people are waking up unsettled and coming to the conclusion that repose is no longer possible and, “if we would save our lives, we must fight for them.”

I suspect that I am not the only person living through these moments who, like Thoreau, finds their dog walks interrupted by the memory that we live “in a country where both the rulers and the ruled are without principle. The remembrance of my country spoils my walk. My thoughts are murder to the State, and involuntarily go plotting against her.”

Radicalization and Foment

In the years between 1830 and 1860, political radicalization was a primary force that transformed the relative repose of the first decades of the United States into the foment, rebellion, and second founding that took place before, during, and after the Civil War. Thoreau and Amos Lawrence were radicalized by Anthony Burns, but nearly every abolitionist had some similar radicalization story. Salmon Chase and Harriet Beecher Stowe were both radicalized by witnessing a violent anti-abolitionist riot in Cincinnati in 1836. Others were radicalized by the violent murder of abolitionist journalist Elijah Lovejoy in 1837. Still others were radicalized by the controversy over the annexation of Texas as a slave state in 1845, and many more were radicalized by the indignities of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 and the attendant movement against it.

Radicalization and polarization were not only happening in opposition to slavery. In the South, slaveholders became increasingly strident in their justifications and defenses of slavery. In response to the Nat Turner uprising of 1831, planters cracked down on oppression both on the plantation and by passing increasingly stringent state laws restricting the movement and limited freedoms of enslaved people. In the years that followed, the reactionary defense of slavery (and paranoia about northern interference) heightened. Southerners suppressed abolitionist speech, passed increasingly harsh laws against manumission, and demanded ever increasing concessions from the North.

The effect of polarization and radicalization was to force people like Thoreau out of their repose and into an active critique of the status quo. These critiques varied widely, even within a given “side” of the slavery question. Some opponents of slavery, like Abraham Lincoln, adopted a position against the expansion of slavery without seeking its abolition. Others, like John Brown, concluded that the fight against slavery required an armed revolution. For some, radicalization did not come until the South seceded and began the civil war while others were radicalized on the battlefield. It was not until all of these streams came together in the midst of the Civil War that the transformational act of emancipation became a political and legal possibility.

The lens of gradual radicalization in the antebellum United States shows an individualized narrative–people slowly changing their political, legal, and social understandings through individual acts of conversion. But if you look collectively you can see that running parallel to this radicalization is a slowly-building roar of foment. As more and more individuals came to understand the status quo sociolegal order as either illegitimate or inadequate, the institutions of that order became unstable. In the late 1840s, the old Whig Party fractured as its members disagreed over the extent to which the slaveocracy should be appeased. As the shards of the old order struggled to maintain order and stability, the foment only grew. The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 was a product of a purported grand compromise intended to appease the South and protect the Union. Instead, the new law inflamed opposition and fueled further and deeper foment. The same was true of the attempted compromises of the Kansas and Nebraska Acts (which led to Bleeding Kansas and the first skirmishes of the Civil War) and the Dred Scott decision (which dealt a body blow to the public legitimacy of the Supreme Court).

By 1860, the old sociolegal order had so crumbled that foment was ascendant everywhere. Radicalization and polarization were abroad on all sides of the political spectrum. The reactionary radicals in the South seceded in an act of violent political imagination, while the Republican party insisted on its own radical vision of a unified nation–a vision that at least limited (and for some abolished) the role of slavery in the economic, social, and political fabric of American life.

It’s easy to see the negative side of this foment. Where there had been a fragile compromise upholding an even more fragile political stability, by 1861 the nation was plunged into a brutal and bloody Civil War. As moderates and defenders of the unsteady old order had argued, foment would mean violence, fracture, and death. On the other hand, it is also easy to see the positive side of this foment. By 1867, millions of formerly enslaved people had been emancipated and the Reconstruction Amendments had been ratified transforming the face of American constitutionalism.

But the question is not whether foment is a good or a bad thing. Today, as it had in the 1850s, foment has come. The question is how we handle it when it arrives. One does not have to celebrate death or violence to understand that the foment that produced the Civil War also opened the doors of possibility for one of the most liberatory transformations in American political, social, and legal life. And although the Reconstruction Amendments themselves were compromises–and although they were soon to be read narrowly by an increasingly reactionary Supreme Court in the increasingly reactionary political climate of Redemption–they were, nonetheless, a tectonic transformation that was only made possible by the foment from which they emerged.

A stable sociolegal order is comfortable and it would be hard to blame people for desiring and striving to protect that order to preserve emotional and material comfort. But as that order becomes porous and fragile, it becomes increasingly likely that those who were comfortable will come to realize that there is no going back to the comfort they felt in the past. This realization is activating and radicalizing. A radicalized society is likely to be a polarized society. And, as we saw in the 1850s, radicalization eats away at the sociolegal order, breeding a political foment which, in turn fuels further radicalization.

History and the Present

At the risk of being fatuous, let me state the obvious: the conditions of radicalization, foment, and transformation that we saw in the 1850s look a great deal like the present. Since the beginning of the 21st Century we’ve been witnessing a steady march of radicalization in our politics as the seemingly stable political order of the mid-20th Century slowly eroded. On the right, we have seen the creeping growth of white supremacy, anarcho-libertarianism, and a politics of fact-averse paranoia. On the left, we’ve seen the growth of economic populism, resistance to structural racial inequality, and steadily decreasing faith in government institutions as vectors of solution or salvation.

Moments of conversion and radicalization are everywhere if you look for them. From Elon Musk’s transformation from normie tech-bro to paranoid white supremacist to Bill Kristol’s transformation from normie conservative to defender of trans rights, people are going to sleep and waking up “stark mad” in all directions. I suspect that fewer and fewer people would describe this moment as “an era of repose,” and for those that might, radicalizations are happening at a frenetic pace. People are losing their jobs, lawful residents are being deported, people are dying of measles and lack of adequate prenatal care, social security benefits are at risk. As radicalization and political activation grow, repose recedes, and it becomes clear that we are living in an era of foment.

As it was in the 1850s, the foment of the present is terrifying. People’s lives and livelihoods are at risk. State actors, invested with the state’s monopoly on violence, openly seek to oppress political opponents, suppress political dissent, and destroy the infrastructure of our civic life. Violence and threat are woven through all of this. People who might otherwise speak out against the administration are being silenced by fear of harm and retribution. People who have spoken out against Trump are being arrested, abused, and threatened with deportation. Even in writing these words as a cis-gendered, straight, white man with tenure, I note my own frisson of anxiety at the shadow of violence that stretches over any work of dissent or challenge to the regime.

But violence and suppression are tools that emerge from anxiety in the midst of instability and change. This is because the flip side of terror is the radical promise and possibility of an era of foment. The old sociolegal order was deeply flawed. It permitted the perpetuation of profound structural inequalities, ongoing oppression, and deeply rooted distributional disparities in wealth, power, and privilege across society. Our constitutional and legal order have not always been liberatory or egalitarian forces (and, perhaps, they have almost never been). Our institutions have not always been bastions of democratic inclusion, fairness, or liberation (and, perhaps, they have almost never been).

With the old order and the old institutions weak and changing, what comes next is deeply uncertain. Having left our era of repose for an era of foment, we “have used up all of our inherited freedom” again–and “if we would save our lives we must fight for them.” Here in the moment of foment that we find ourselves, the question we face is what we should be doing to fight–for what, with whom, and how?

Becoming Founders

In 1862, Albion Tourgée was convalescing on a Unionist (i.e. not in favor of secession) plantation in Kentucky after having been injured at the first Battle of Bull Run. Tourgée was in many ways a typical Union soldier. He had enlisted out of nationalist fervor and held mildly anti-slavery views, but he was fighting not for revolution, but to protect the old order. After experiencing the brutality of the war and then after spending months living among enslaved people on the plantation, Tourgée was activated and radicalized. In 1863 he wrote a letter home that echoed Thoreau, “my brain throbs–my blood boils! I cannot forget what has occurred.” No longer satisfied with fighting for the preservation of the Union, Tourgée rejected backward looking politics and embraced a founder’s energy: “I don’t care a rag for the ‘Union as it was.’ I want to fight for the Union ‘better than it was.’ Before this can be accomplished we must have . . . a thorough and complete revolution.”

When the war was over, Tourgée put his money (and his life) where his mouth was. He moved south to North Carolina where he became one of the primary architects of that state’s 1868 Reconstruction Constitution. In a quite literal sense, in an era of foment, Tourgée became a founder.

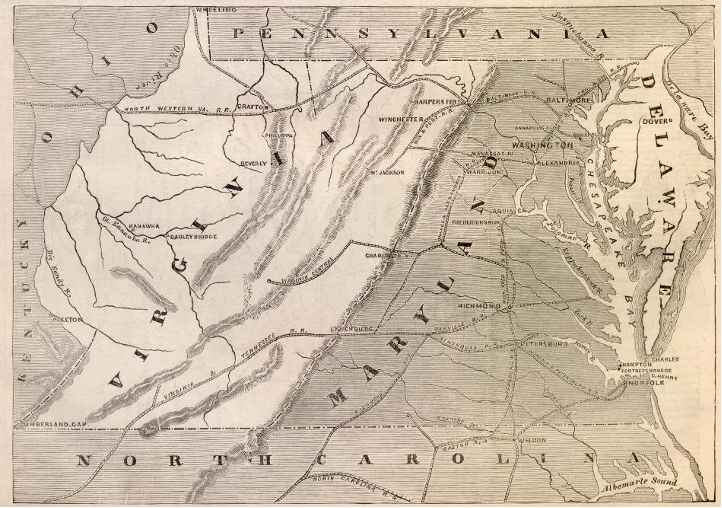

He wasn’t alone. Across the 1850s and 60s, fundamental reimaginations of American political life flourished. Secessionists and Confederates, of course, proposed to found a new nation to protect slavery and the “southern way of life.” In response, abolitionists and unionists engaged their own founding imaginations. Radical Republican congressman Thaddeus Stevens and others called for confederate land to be confiscated and redistributed, arguing that “the whole fabric of southern society must be changed.” Abolitionist firebrand Wendell Phillips argued that the Civil War would not be won until the North had “ma[de] over the South in its likeness, till South Carolina gravitates by natural tendency to New England.” General Simon Cameron argued that the borders of Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia should be redrawn to punish Virginians for secession and dilute the voting strength of slave owners.

Others argued for more far-reaching redrawing of state lines. Richard Hildreth (an abolitionist lawyer and historian who had been made consul to Treiste) suggested that Florida and Texas be subdivided, that Alabama and Mississippi lose their ports, and that a new state of Appalachia be carved out of Virginia and the Carolinas.

I could go on, and on, and on. In the foment of the mid 19th Century, everything was up for grabs. Amid the rubble of the old order, politics meant fighting for something new–for a Union “better than it was.” Ideas that had been unthinkable under the old order–secession, emancipation, land reform, enfranchisement–became objects of legitimate and mainstream political dispute.

In this cauldron, the old politics of stability and compromise were burned away and replaced by a politics of founding.

Moments of foment overlap with moments of founding. Whether you look only at the formal “founding” moments of Constitutional adjustment (1787, 1867) or whether you look more broadly at more informal “constitutional moments” (Ackerman, Balkin/Levinson, etc.), our sociolegal order has been subject to radical change and transformation where the repose of stability was replaced by instability and contention.

This foment that we find ourselves in is no different. Whether we like it or not, everyone participating in American politics right now is a participant in a process of a new founding. When I say “participating,” I mean this inclusively. I mean voters, consumers, readers of the newspaper, readers of conspiracy theories, immigrants, and everyone outside of the formal borders of the nation who is invested in and implicated by what is happening here. Under this formulation, we are all founders, and we have no choice but to be.

Whether we like it or not, the foundations of a new sociolegal order are being constructed around us. Our old institutions are not going to save us and will only be useful to us insofar as we invest them with present utility and meaning. Even if we wanted to simply reconstitute the old sociolegal order, it is too late. There is no going back. Whatever emerges from this moment will be something new that we will have built together. This is why none of us have a choice about whether or not to be founders. We are building together whether we are active or passive, whether we are activated or inert, whether we are politicized or apathetic. In this context, neutrality is a fantasy–as is adherence to the status quo. In reality, we are all in motion and what choices we make amid the foment matter whether we like it or not.

One way of re-describing the conversion from repose to radicalism is as an awakening to the reality that the foment of the present has transformed us into founders. This was true for Thoreau and Amos Lawrence, and increasingly it is true in our present politics. As people become activated, the language of mainstream politics is transforming from one of preservation to one of imagination and alternatives. It is not sufficient to simply demand that the machinery of our institutions do their work. We must be asking about the values, virtues, and purposes of those institutions themselves.

Founding, Participation, Democracy, and Optimism

If we have no choice but to be founders in this era of foment, then it is incumbent upon us to understand what founding means. All too often we think of the moments of “founding” as snapshots of inert heroism. The “founding fathers” of the 1787 constitution are lionized (sometimes in regressive ways, sometimes in progressive ways). Though the hagiography is less widespread, the same is true of the “founding fathers” of the Reconstruction Amendments. Too often, “the founding” is construed as an inert act of the past, undertaken by men (always white men) which produced the quasi-sacred constitutional text. Under this understanding, founding is something that other people do, and founders are historical actors whose words we parse.

In this moment of anxiety and instability, it’s not surprising that some people would like to rely on the old founders as a bulwark of repose. Last year, we saw people reaching for the 14th Amendment to disqualify Donald Trump as an insurrectionist, and now in court we see it being invoked to protect birthright citizenship and free speech.

While a turn to the old founders is understandable–and while invocations of heroic voices can be strategically useful–looking backward cannot be an excuse to abdicate our present responsibility. We are in a moment where things that were settled have become unsettled and where things that were uncontested have become contested. The founders are not walking through that door. Whether we like it or not, in the rubble of the old order, we are the ones who will be building the new order together.

This sounds like hard work, and it is. But it’s also profoundly optimistic. A politics of founding is a politics of thick and generative public participation. It is a politics where we see democracy as more than elections and law as more than an external set of rules and constraints. Amid the foment, the work we do together to struggle and resist is daily work in our communities, within our institutions, and among ourselves. Everywhere and anywhere is civic and political space. The whole fabric of public life is subject to reimagination and negotiation. In a world where so much is up for grabs, the political stakes of the daily reality of moving through the world are made clear. When we have no choice but to be founders we have no choice but to be active participants in our civic lives.

Becoming founders is also empowering. In a well-functioning democracy, we should not be beholden to the political imaginations of long-dead people with values that were at best foreign and at worst anathema to ours. Self-governance means not only adherence to our antique constitution, but also the power and authority to imagine our own politics for ourselves. In an era of repose, it can be easy to forget that we have always been founders if we wanted to be. In the trauma and alarm of the foment of the present, we no longer have the luxury of forgetting this. We have used up our inherited freedom, and if we want to live in a better world, we must build it together.

To make the abstract concrete, just a few salient examples from the headlines demonstrate the way in which the exigent choices that we make every day have become invested with foundational significance. When a university agrees to be obedient to the regime, it is helping define the meaning of academic freedom going forward. When a law firm cuts a deal with bullies, it is helping to define the professional role of lawyers going forward. By the same token acts that would have seemed merely normal in an era of repose take on a revolutionary character. When a middle school teacher stands up and helps define the meaning of democracy in a classroom, a seemingly normal act of humanity is transformed into an act of dissident political imagination. When a second-year law firm associate writes a resignation email, it galvanizes a reexamination of the values and political economy of the legal profession.

These are examples of people and institutions seeking to live “normal” lives amidst the turmoil of foment. One might look at all these instances and see a latent desire to return to an old order–one where you could simply make money, cooperate with the government, respect all voices, and balance profession and principle. But that old order is gone and even the desire to return to it is transformed whether we like it or not into a desire to found–or to refound a new order.

One need not look far to find people who are explicitly stating truly foundational visions for remaking American life. From Project 2025, to the Green New Deal, to “abundance,” to a third reconstruction. Likewise, one need not look far to find people imagining redrawn national boundaries and reformulated national identities.

But you don’t have to write a think piece or start a revolution to be a founder right now. We are all making it up as we go along together. Whether we like it or not, our own personal and multiple ideas of what our sociolegal order should be have become a part of the politics of this moment. We have reached this era of foment precisely because we do not all share the same ideas–and this dissensus is both scary and thrilling. Whatever will come from this foment will be made by us through our actions and inactions, through our mistakes and our bravery. To some degree, of course, this has always been true. But here, having sloughed off our era of repose, and having used up all of our inherited freedoms, we have no choice but to see how our daily actions are constitutive of the world that we are building together. Amidst all the chaos, stupidity, cruelty, and anxiety of the present, the reality that we are all founders may be a raft of optimism. At the very least it is a reminder that we are not powerless. Whatever comes next will be built out of our collective struggle and imagination.